By Oriiz U Onuwaje

Oriiz presents a simple truth for today: rhythm is evidence. Rhythm preserves a people’s story, reveals intelligence, and brings order. The beat is more than music for dancing; it captures life itself. Dance does more than entertain; it bears witness. Before museums and libraries, Africans kept their heritage alive by repeating steps until they became traditions. Now, as the world turns to African rhythms, this living archive endures.

Rhythm Before Paper

Today, many people see rhythm as pure enjoyment. They dance to it, unwind after work, or use it as background music on weekends. But in many African cultures, rhythm has always been more than for fun. It has always meant more. Rhythm was proof.

It showed intelligence. It showed order. It showed memory. These qualities demonstrated that people remained strong, expressive, and confident. Rhythm is one of Africa’s oldest and strongest archives because people never kept it in buildings; they kept it in people.

Rhythm came before paper, museums, and libraries. Before written records were common, many African societies used repetition to pass on identity. The drum, the dance step, the chant, the circle, the response, and the pattern served purposes beyond decoration. The drums were ways to keep culture alive.

The Body as Archive

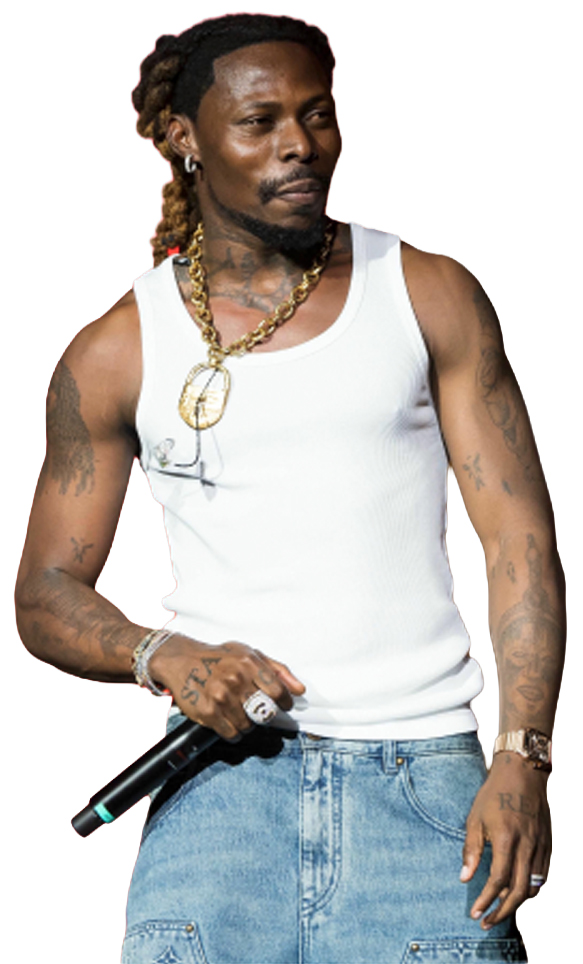

Asake

Asake

The deep connection between rhythm and the body makes African rhythm so special. It moves both the ears and the body. Even if people find the words unfamiliar, their bodies still understand. Shoulders respond, hips follow, and feet find the beat. The head nods before the mind knows why. This reaction does not happen by chance; it has been preserved by generations.

At its core, rhythm is organised time. It’s discipline. It’s structure you can hear. It’s maths in motion. Rhythm teaches the body how to move with order: when to enter, when to pause, when to lead, and when to follow. In African traditions, rhythm was more than sound. It stood as a lesson.

Dance was always more than about self-expression. It was memory you could see.

Each step held memory. Each sequence revealed identity. Every formation made shared knowledge clear. When people wrote little, the body became the record. When paper could be destroyed, the body kept the memory safe. When history was denied, the body spoke up.

African dance traditions usually emphasise togetherness, patterns, and circles, with call-and-response movements. They use repetition, not out of laziness, but to preserve what matters. By repeating, cultures keep what matters alive. A society keeps repeating what it can’t risk losing.

The Drum Was Governance

In many African societies, people used rhythm to express what they could not say in private. Rhythm marked rites of passage, honoured elders, and remembered ancestors. Communities set moral boundaries and conveyed grief, joy, protest, and renewal through rhythm. Sometimes people used rhythm to show power, warn of danger, or unite the community. Rhythm achieved all this because it spoke without words.

Tony Allen

Because rhythm was so important, drums were never ordinary instruments. Across Africa, people used drums to communicate, not just to make music. Drummers sent messages over long distances, announced arrivals and departures, signalled danger or ceremonies, and shared praise names, often representing the authority of leaders. The drum spoke, and people respected it as much as spoken words.

Rhythm lasts because it moves from place to place.

Empires can burn buildings, take away objects, and silence books. But how can anyone take what lives in people’s blood? How can you stop a heartbeat? How can you capture a memory once it’s become part of the body?

One of Africa’s greatest strengths is that its archives weren’t kept on shelves. They were alive. Even in hard times, the rhythm stayed strong.

It’s no stretch to say that rhythm helped African civilisation survive major disruptions. Colonial invasions aimed to erase culture, not just seize power. They attacked languages, spiritual beliefs, and local education. They wanted Africans to forget their past and lose confidence in their future.

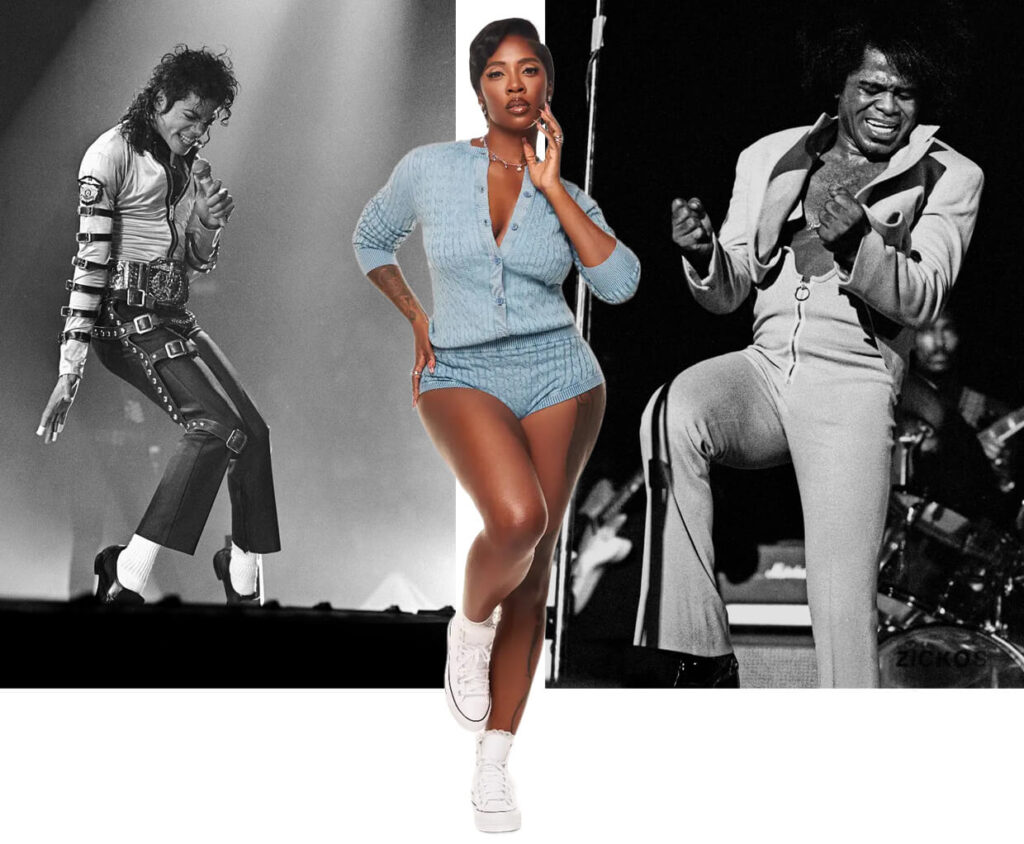

Tems and Rema

But rhythm endured. The `Ring Shout` among enslaved people in the Americas clearly shows this. In this tradition, people moved in a circle, sang back and forth, and used rhythm to keep West African culture alive, even under harsh oppression.

Rhythm survives because people carry it in their bodies. The body is the safest archive, always there. People don’t need permission to exist or approval to keep rhythm alive. They perform it in secret, take it with them when they leave home, rebuild it in new places, and share it with their children through happiness.

Heritage in Motion: The Global Proof

Because rhythm survived loss and displacement, it became a way to rebuild in the diaspora. Even when enslaved Africans lost their names, families, homes, and histories, rhythm stayed. Movement stayed. The beat stayed. When memory was threatened, rhythm helped people find themselves again.

So, dance wasn’t just for fun. Dance was healing. Dance was protest. Dance was a way to make a home. Dance was a way to say, “We are still here.”

Rhythm is key to African modern life. Today, people often think of modernity as machines, but Africa’s version is deeper. It’s about intelligence, systems, adaptation, and keeping traditions alive in ways that endure.

Rhythm works much like technology. It processes, shares, copies, and updates itself. It keeps identity alive from generation to generation, even when external systems fall apart. Like good technology, rhythm has backups, so meaning isn’t lost if one way fails. It can be in a voice, a drum, a clap, a footstep, a chant, or even silence. Rhythm doesn’t depend on one thing; it lives in the whole community.

The worldwide love for African rhythms says a lot about today’s culture. African rhythms now dominate popular music worldwide, from Afrobeats to Amapiano to Afro-fusion. Some call it a trend or a genre, but it’s really tradition coming through loud and clear.

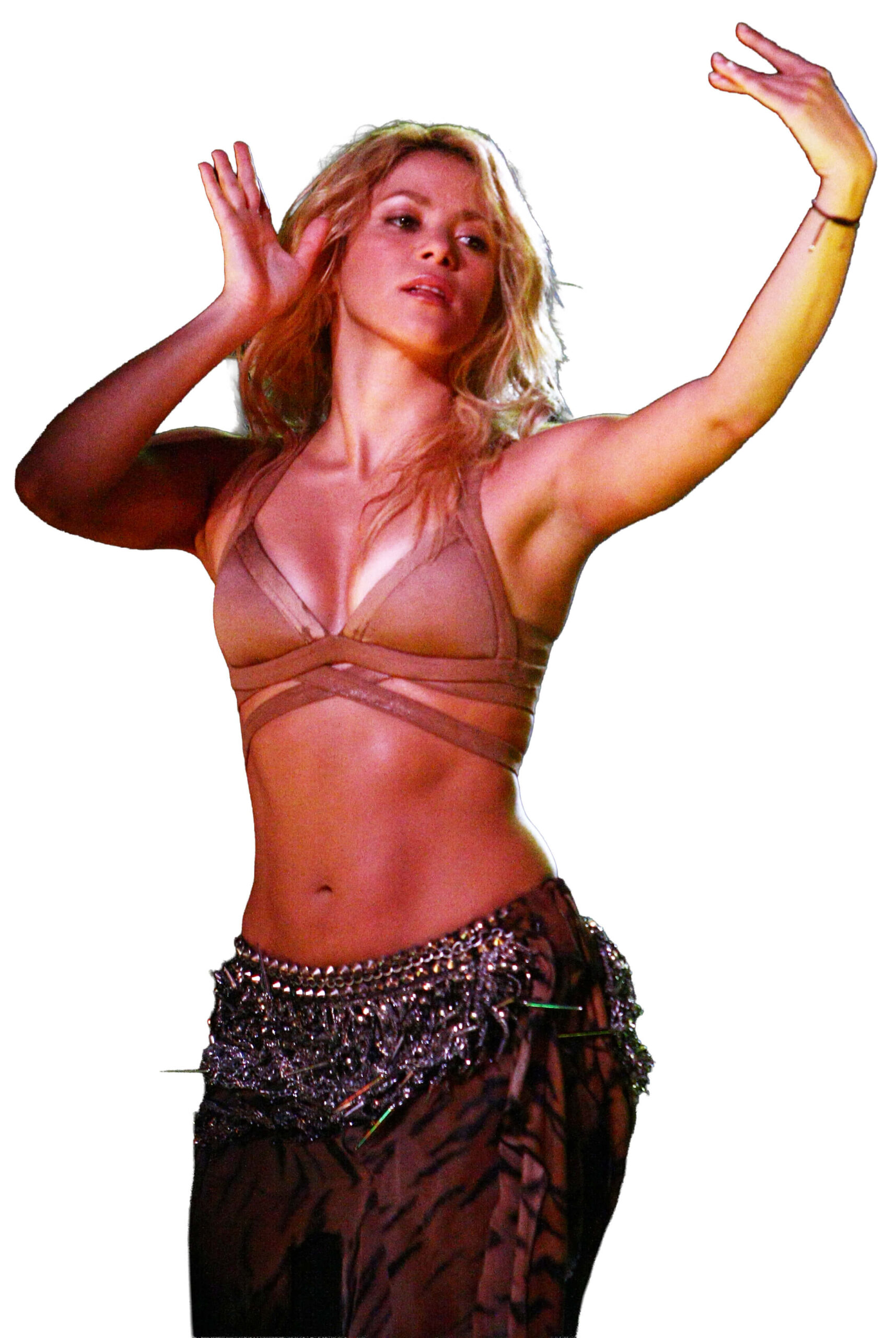

You can see this in how top performers treat rhythm as a powerful force. James Brown created a whole style from footwork, timing, and call-and-response. Michael Jackson turned precision into a ritual, using sharp moves and pauses as a form of discipline. Even Shakira’s way of moving shows that rhythm is a language before it’s ever words.

Shakira

And the proof is not only outside Africa. It is at home. Artists such as Burna Boy and Davido embody the communal, festival energy of the rhythm, a collective archive in motion. In contrast, Wizkid’s meticulousness or the late Michael Jackson’s demonstrates rhythm’s function as order and discipline. The powerful presence of artists such as Tiwa Savage and Tems shows how the archive lives in aura and posture, not just movement. Ayra Starr dances like youth discovering its inheritance in real time. Yemi Alade carries stage movement like a visible percussion rhythm. Tyla turns contemporary pop into an African pulse you can see.

Afrobeats isn’t just music. It’s heritage in motion. It’s like learning a new language. It’s old wisdom in a modern style. It’s Africa showing the world not by arguing but by clear proof that it has always shaped culture.

Why Rhythm Matters Now

The world responds because the body doesn’t lie. You can question a book, doubt a museum label, or argue about a story. But when rhythm moves you, the truth is felt. Rhythm proves itself.

The strong link between rhythm and identity shows why rhythm matters beyond performance. Rhythm shapes who people are, their confidence, and even their sense of nationhood. For African societies and the diaspora, when a society forgets its rhythm, it loses its inner order. It loses the patterns and ways of connection that once fostered belonging and held it together. Without this inner archive, people are more likely to adopt external identities and meanings.

When people reconnect with African rhythms, they aren’t merely looking back with sentimental longing. They find proof, regain wisdom, and realise their traditions never ended; they simply changed form.

African rhythm stands out because it moves both the ears and the body. Even when people do not recognise the words, their bodies still understand. Shoulders respond, hips follow, and feet find the beat. The head nods before the mind knows why. This reaction comes from generations who preserved it, not from random chance.

Rhythm isn’t just something Africans are good at.

Rhythm is what keeps Africa true to itself.

Rhythm is proof.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history portable and accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask. He connects 8,000 years of knowledge to the present.