From sacred clay to algorithmic code

What does it mean to capture the likeness of a soul, whether using sacred earth or lines of code?

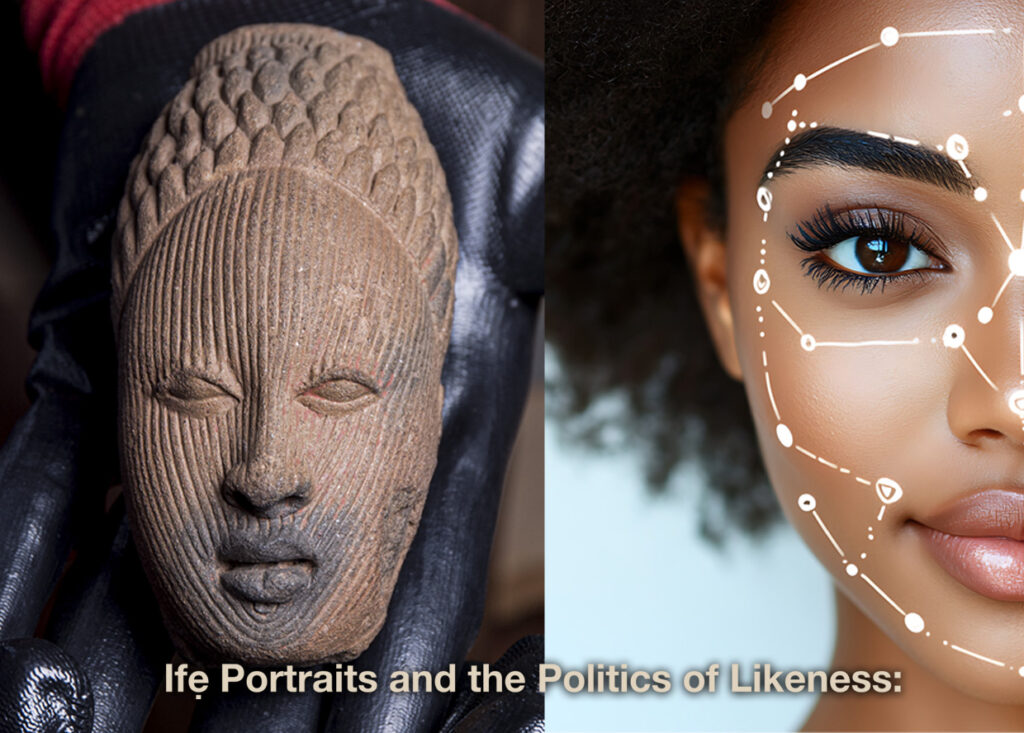

Oriiz looks at how capturing likeness has always been a political act, from the ritual workshops of ancient Ifẹ to today’s AI systems that shape our identities.

Form is never neutral. A thousand years ago in Ifẹ — Nigeria, artists sculpted faces in bronze and terracotta with such skill that early European visitors doubted Africans could have made them. These works were more than just effigies; they declared existence. They showed that identity could be portrayed with dignity, accuracy, and real presence. The artists captured not only the shape of a face, but also the essence of a person.

Imagine a terracotta head, smaller than a clenched fist. The sculptor made it so lifelike that it feels like a moment frozen in time, not just a simple image. The fine lines of the hair, the gentle fullness of the lips, and the calm authority in the eyes are all crafted with such care that the terracotta seems almost alive. These works feel magical because they carry a person’s presence across centuries.

Today, artificial intelligence has a similar goal: to read, classify, and copy the human face. But making a likeness, whether from sacred clay or complex code, is never simple. It always brings cultural, political, and ethical consequences. From ancient Ifẹ shrines to Silicon Valley datasets, creating likeness is still a struggle over meaning, visibility, and power.

The naturalism in Ifẹ portraiture was intentional. Made between the 12th and 15th centuries, these works show careful attention to life: detailed hairstyles, intricate crowns, and gentle cheekbones. This realism served a purpose beyond beauty. In a society where sacred kingship connected the mortal and the divine, a portrait anchored spiritual presence. It made rulers or ancestors present, linking the living to their lineage and legitimacy.

Being shown in such detail meant being truly *seen*, acknowledged, remembered, and given authority in the kingdom’s worldview. The portrait did not just reflect identity; it helped create and confirm it.

A thousand years later, artificial intelligence attempts to interpret human faces using algorithms and machine learning. These systems classify expressions, verify identities, and create synthetic faces. These systems, too, claim the ability to capture “likeness.” Yet today, the stakes are far greater. Ifẹ artists approached their craft with ritual respect, whereas AI is frequently employed for surveillance, commerce, and social control. An error in ancient Ifẹ might have altered a narrative, but an error in an AI system now can threaten a person’s freedom, opportunity, or safety.

We cannot ignore the politics behind this act of seeing. In Ifẹ, bronzes were made in a world where representation affirmed belonging, ancestry, and authority, making sure people were included. In contrast, the “eyes” of AI are shaped by datasets that often exclude or misrepresent African faces, leading to a modern form of erasure. Research shows facial recognition technology fails to identify people of African descent much more often than it does for Caucasians. This is not just a technical flaw; it is the digital echo of historical marginalization. When the code cannot see you, the systems built with it deny your full humanity.

Still, both worlds share a common goal. Ifẹ artists wanted to honor their subjects with honest and respectful representation. Today, many technologists try to build fairer and more inclusive systems. The deeper lesson from Ifẹ is that true likeness is not just about technical accuracy. It is a relational, contextual, and moral task—a question of how a face is understood, placed, and valued. The ethical challenge is whether AI can learn to respect cultural sovereignty and community agency, and approach the work with the same care that Ifẹ sculptors gave their subjects.

The materials themselves tell a story. Ifẹ works were made from earth, metal, and fire, shaped by human skill into lasting vessels of memory. The medium was sacred.

In contrast, AI is built from code, silicon, and electricity. Its materials are invisible but just as powerful. A dataset is never a neutral picture of the world; it is a record of power, highlighting some stories and hiding others.

An algorithm always reflects the biases and blind spots of its creators. The base material of AI is not bronze, but often unexamined bias. Without careful questioning, it can create likenesses that reinforce injustice.

But this new medium also has the power to transform. Just as Ifẹ portraits preserved identity over time, AI can help reclaim history. Today, artists across Africa and its diaspora use AI to reinterpret traditional forms, create imagined portraits of ancestors, and challenge colonial archives. In their hands, AI becomes a digital tool for shaping new futures from African memory.

For example, Afrofuturist artists use generative models to create portraits that mix Ifẹ’s naturalism with bold, imaginative styles: skin like liquid metal, headdresses with geometric patterns, and faces that suggest entire worlds. These works reject the idea that African innovation belongs only to the past. They carry Ifẹ’s realism into the future, showing that technological creativity is an ongoing and vital tradition.

Yet this potential also brings risks. Algorithmic likeness is already used for surveillance, border enforcement, and spreading political disinformation through deepfakes. Artificial faces can overshadow real ones, and mistakes can reinforce harmful stereotypes. Like any powerful technology, AI must be guided by strong ethical standards. Ifẹ artists were bound by a culture that valued dignity above all else. For AI, the key question is not whether it can copy the form, but whether it can be guided by the same deep sense of responsibility.

A dialogue between an ancient terracotta head and a modern algorithm reveals a lasting truth: likeness is far more than a mere image—it is the site where power and identity are negotiated.

Ifẹ sculptors relied on ritual, lineage, and skilled hands; today’s AI engineers build with code, data, and logic. Both professions determine how people are represented—and, in turn, how they are allowed to exist in the world.

This raises a crucial question: Who holds the right to likeness? In Ifẹ, that authority rested with the community, shaped by shared cultural meaning. Now, that power often lies with corporations and governments. The struggle for fair and just likeness is ultimately a struggle for autonomy, recognition, and the essential, almost magical right to be seen and to exist.

The unBROKEN Thread links the calm, striking faces of Ifẹ to the digital faces made by neural networks. It reminds us that wanting to preserve and understand identity through technology is deeply human. It urges us to approach every likeness, whether made in clay or coded in silicon, with intention, integrity, and the goal that representation always brings dignity, not erasure.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask, connecting 8,000 years of knowledge to today.