By Oriiz U Onuwaje

Oriiz views design as more than decoration. He sees it as a tool that shapes and stabilises power, identity, and continuity. Throughout history, people have used objects for more than beauty. They use form to pass on memory, organise authority, and make hidden systems visible. What we now call design innovation is part of a long tradition: shaping materials to carry meaning across time and place.

Continuity in Design Intelligence

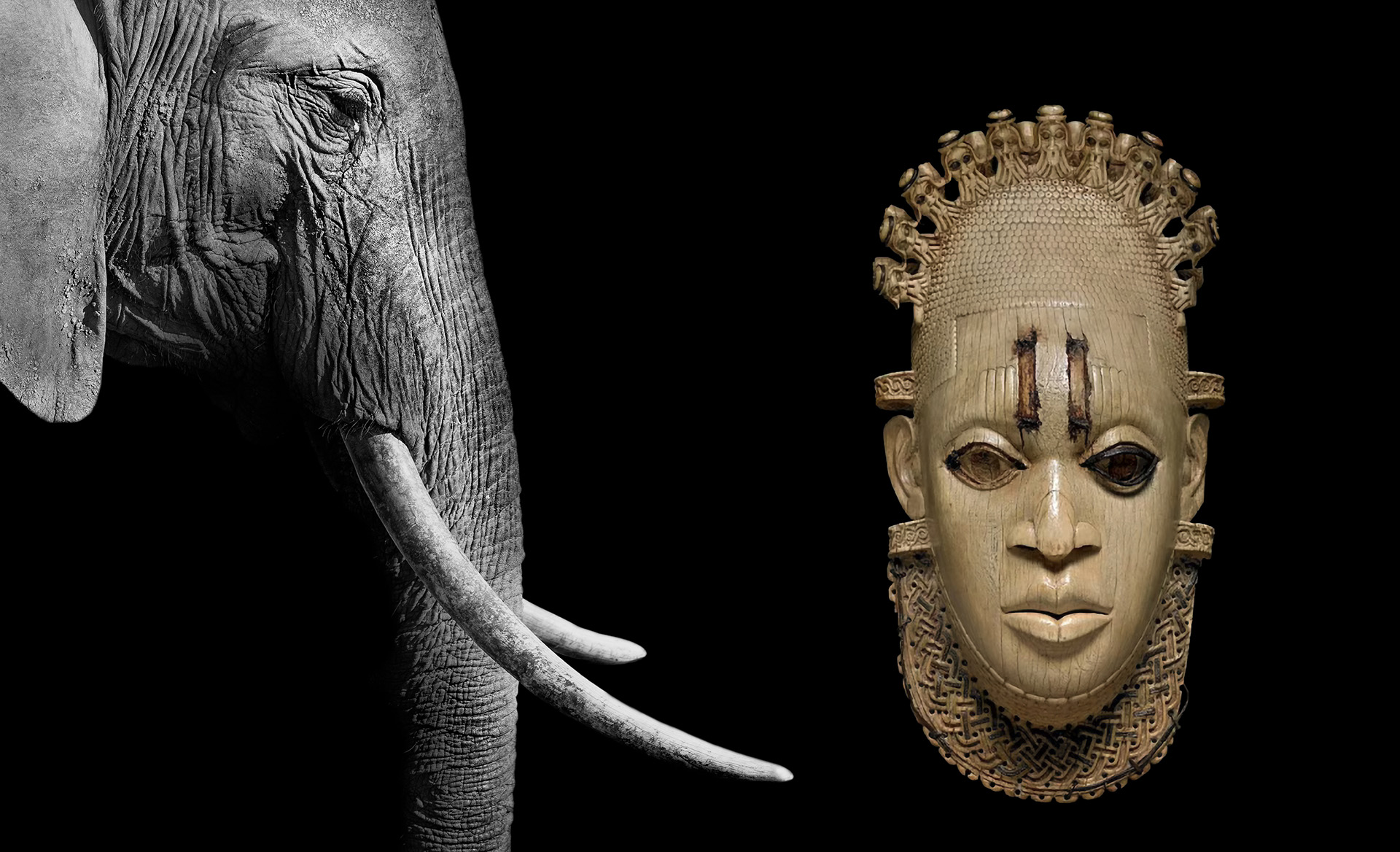

Five centuries ago in Benin, court artists addressed this challenge in ivory. Today, designers address it in glass, silicon, and metal. The contexts differ. The materials differ. But the underlying ambition is strikingly similar. It is the desire to engineer form to hold power, project identity, and mediate connection past the immediate moment.

Although separated by five centuries, designers in Benin and today face the same challenge: making form carry power, identity, and connection across time and space. The materials are different, but the thinking behind the design remains the same. Time separates them, not their design intelligence.

Benin, Authority, and Engineered Form

In the early sixteenth century, this design intelligence found one of its most refined expressions in the Kingdom of Benin, in present-day Nigeria. There, artists working within the royal court produced objects that were not exclusively ceremonial but were structurally embedded in governance, spirituality, and political identity. Among the most extraordinary of these works are the ivory pendant masks associated with Queen Idia, the Iyoba, or Queen Mother, a strong strategist whose counsel and political wisdom were instrumental in securing the reign of her son, Oba Esigie, during a period of internal conflict and external threat. Her role was active, decisive, and foundational to the kingdom’s stability.

The masks made to honour her were not just simple portraits. They were carefully crafted tools of leadership. The Oba wore them during key ceremonies to affirm lineage and clarify authority, linking political power to maternal heritage and family continuity. These objects fit into the court’s complex traditions. They served as spiritual tools, political symbols, and wearable signs of royal legitimacy.

Guild Systems and the Discipline of Continuity

This level of skill did not come from one person’s talent alone. It came from a well-organised design system within the Benin court. Artists who carved royal ivory, especially those in the Igbesanmwan guild, followed strict rules. Their job was not to express themselves, but to turn royal authority into physical form with discipline. Rules about proportions, symbols, and designs kept the style consistent over generations. This system ensured that power was always presented clearly and consistently.

The fact that several Queen Idia masks still exist today shows how strong this system was. The masks are not exact copies, but they share a clear style. There are small differences, but all within set rules. This consistency shows a workshop culture grounded in standards, careful supervision, and the passing down of skills. Even before the term ‘industrial design’ was used, Benin’s guilds understood that authority relies on reliable quality. The form had to be steady enough to be recognised, but still lively enough to have presence. This balance was intentional.

Material Hierarchy and the Meaning of Ivory

In the Benin court, the choice of materials was always deliberate and meaningful. Ivory, which is bright and rare, stood for purity, prestige, and spiritual power. Its light colour reflected light in a special way, making carvings seem to glow during rituals. Using ivory for royal and ancestral objects imbued the material with a sense of hierarchy. The meaning was part of the substance itself.

This idea is still important in design today. Some materials are chosen for objects meant to last, stand out, or show high status. The choice affects both how things look and how they feel. Materials influence how people see, touch, and value an object. In Benin, ivory was used because it could carry both deep meaning and a strong physical presence. It made authority feel real.

Choosing ivory for the Queen Idia masks made them even more important as symbols of royal legitimacy. The material showed that these were not ordinary items, but objects connected to the heart of the kingdom’s spiritual and political life. With choices like this, design became more than just looks—it became a way to show hierarchy, tradition, and belief.

Design as Mediation Betwixt Worlds

The design skill seen in the Benin court was not limited to its own time. It addressed a problem that still exists: how can form represent larger systems? Objects that last are rarely just neutral things. They help build trust, show identity, and give shape to things people can’t always see. In any society, design helps make authority clear and continuity visible.

What changes over time is not the purpose of design, but the world it works in. As societies become more complex, the hidden systems that shape daily life grow as well. These systems have shifted from spiritual beliefs and royal families to financial networks, digital systems, and global communication. Designers still work where people meet these big, unseen forces. Their job is much the same: to shape materials that connect individuals to what they cannot see.

The Contemporary Interface

Few modern objects show this ongoing design challenge as well as the smartphone. Made to be carried everywhere and used all the time, it has become the main link between people and the complex systems that shape our lives. Through smartphones, people connect to communication, money, social identity, and huge amounts of information beyond what they can see. It is more than just a device—it connects human experience to hidden systems.

These objects matter not just for what they do, but also for how they are designed. They are made to feel easy to use, reliable, and personal. Their materials, shapes, and appearance are carefully chosen to help people build a lasting connection with them. In this way, today’s devices follow the same design thinking as Benin’s court artists long ago. The form helps connect people to systems of power, meaning, and relationships that go beyond what we can see.

The iPhone as a Contemporary Example

The iPhone stands out as a clear example of this design culture. Its consistent look around the world, careful design, and role as a daily companion for millions show how much design shapes identity and interaction today. Its importance is not just about being new. It continues an old human goal: making objects that hold meaning, build trust, and move between different settings without losing their identity or authority.

Like the Benin court, which used a set visual style to keep power recognisable, today’s design systems rely on consistency to build trust and familiarity, even across great distances. The scale and networks are bigger now, but the main design ideas are the same. Form is not just something to look at. It actively shapes how people experience the world.

Global Circulation and Systems of Value

The travels of these objects show that design can go beyond its first home. Today, Queen Idia masks are in major museums around the world, seen as great works of human creativity rather than oddities. Their movement raises tough questions about history and ownership, but their place in global museums also shows the lasting power of their design. They still draw attention, respect, and authority far from where they were made.

In another sense, today’s devices circulate through global markets as markers of technology and social status. They work in business systems, not rituals, but both kinds of objects show that design can cross cultures and settings while keeping its power. When form brings together meaning, material, and identity, it can travel and fit into new systems without losing what makes it special.

The Unbroken Logic of Design

Comparing a Queen Idia mask and a modern smartphone is not just about technology. It shows a shared way of thinking. Both come from design traditions that use form to carry hidden meanings. Both show how objects can connect people to bigger systems. They remind us that design is not just about looks or use, but about shaping power, identity, and lasting connections.

Materials have changed. The size and settings have changed. But the main ideas behind design have stayed much the same. For five hundred years, designers have faced the same challenge: making form hold meaning, making material carry memory, and creating objects that can move through time and place without losing their power.

In this way, design is like a language for civilisations. Its rules remain in effect, even when the materials change.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history portable and accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask. He connects 8,000 years of knowledge with the present. Oriiz also edited and served as Executive Producer for The Benin Monarchy: An Anthology of Benin History (The Benin Red Book), Wells Crimson, 2019.

::::::::oriiz@orature.africaIG – @oriizonuwaje