Oriiz shows us how African societies deliberately built memory right into their surroundings. They used design thinking as a way to survive, weaving authority, lineage and continuity into bronze, ivory and wood. What we now admire as art started out as a practical system. People designed these objects to organise history, legitimise power and preserve identity.

Most of us think of memory as something fragile, but these societies made it strong. They wove memory into everyday life, into how they governed, practised rituals and organised their communities. By choosing materials like bronze, ivory and wood, they made sure that memory would last, authority would hold steady and continuity would stretch across generations. In their world, art and life went hand in hand, and every object helped keep identity alive and protected, year after year.

MEMORY AS INFRASTRUCTURE:

Memory is not a whisper.

It is a structure.

It carries weight.

Not a tale told once,

but form repeated

until repetition becomes law.

What a people build to remember

outlives the moment of building.

Fired clay outlives breath. Form outlives fear.

Bronze outlives kings. Form outlives power.

Memory is how a society

refuses erasure,

and names that refusal civilisation.

In many African civilisations, power wasn’t just an idea; it was something people could see and touch. Authority needed form, memory needed structure, and identity needed something solid. These needs led to material traditions that served as archives long before modern record-keeping. Through carving, casting, and building, African societies made memory part of the physical world so that history could be seen, touched, and experienced.

NOT DECORATION:

This was not made

to please the eye.

It was made to hold a kingdom.

Power was carved into matter.

Order was cast into metal.

Authority was given a body.

Beauty was discipline.

Discipline made memory endure.

Endurance became history.

Form was never ornament.

Form was governance made visible.

In Benin’s royal courts, bronze demonstrated that beauty was also power. The bronze plaques brought history to life by recording important events directly onto their surfaces. Arranged in sequence, they told the stories of kings, court ranks, diplomacy, military campaigns and rituals, transforming the palace into a visual archive. These works were designed to be read as records as much as admired for their artistry.

THE FACE OF AUTHORITY:

The face is not a portrait.

It is a philosophy.

It teaches without speaking.

Calm is not softness.

It is controlled power.

Stillness is strength.

When order lives on the surface,

Chaos cannot enter the centre.

Authority begins in form.

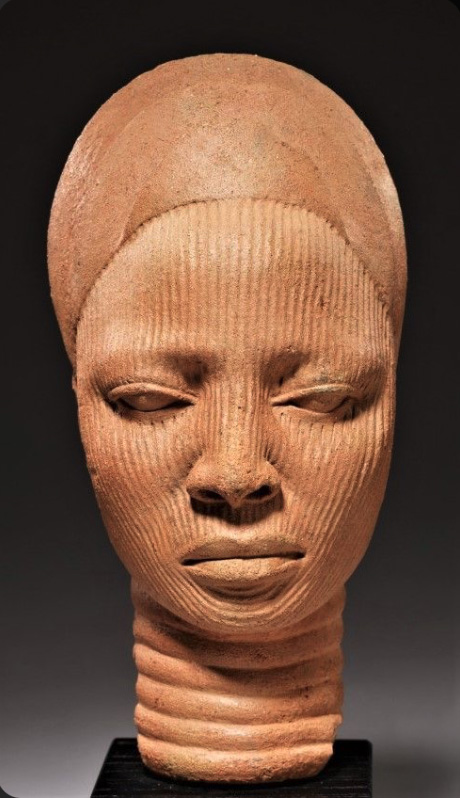

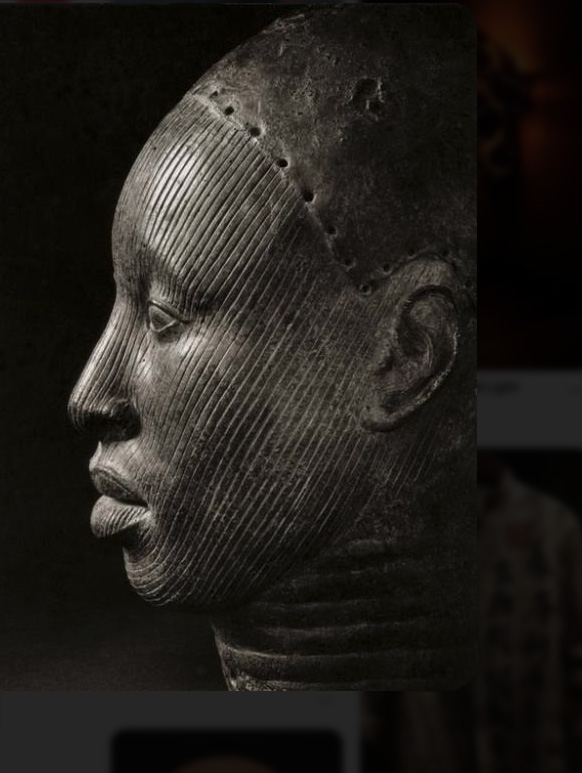

Benin was not the only place with this kind of material knowledge. In Ife, artists produced bronze and terracotta works with remarkable naturalism centuries earlier. The famous Ife heads weren’t merely decorative. They represented sacred kingship and spiritual presence. Their smooth surfaces, balanced forms, and calm expressions embodied ideals of divine rule and moral order. These works gave political authority a visible and lasting form, linking leadership to spiritual beliefs.

Across West Africa and beyond, artists developed ways to express identity, status, and spiritual meaning through the human form. The parallel lines on Ife bronzes and terracottas, often seen as decoration, actually represent facial marks that indicate lineage, community, and social rank. In sculpture, these lines become a calm, idealised visual code rather than a direct portrait.

This way of treating the surface does more than show a face; it shapes it. The careful lines soften the light, reduce distractions, and make the face look calm, conveying steady, centred authority. Other African traditions use pattern, texture, and surface order to show refinement, ancestral presence, or sacred status. These formal systems turn figures into enduring symbols. Identity, spirituality, and leadership are built into material form.

OBJECTS OF GOVERNMENT:

These were not mere things.

They were instructions.

Guides for living.

How to lead.

How to belong.

How to remember.

Law was shaped before it was written.

Order was held before it was spoken.

A people who build their values

in bronze, wood and ivory

do not surrender them easily.

What is carved into matter

outlives the moods of men.

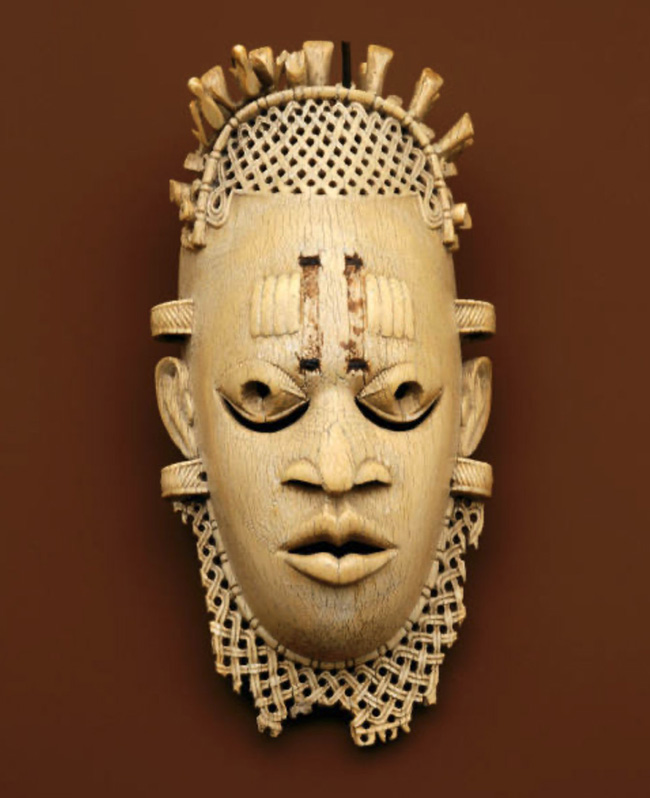

Ivory held similar importance in many African courts. Like bronze in Benin, carved ivory tusks, armlets, and ritual objects were more than signs of wealth. They embodied lineage and sacred authority. Ivory, like bronze, connected the living to their ancestors and linked political order to spiritual life. Its presence in shrines and palaces made memory part of daily life. With ivory, ancestry was always present, and memory was a constant part of experience.

Wood carried the burden of memory throughout Africa. Carved doors, posts, stools, masks, and figures held social knowledge. A carved door could tell a family’s origin story. A stool could represent a chief ’s authority. A mask could embody a community’s moral codes and come to life in ceremonies.

These objects weren’t just separate works of art. They were part of broader systems of education, ritual, and leadership. They were taught through repeated use. They reinforced values through daily use. They made abstract ideas clear and memorable. Their main purpose was to maintain identity, preserve order, and make history difficult to erase.

BEHIND GLASS:

Behind glass, it is called art.

In its home, it was law.

Function turned into display.

A silenced surface.

A separated memory.

A context removed.

The object survived.

The system was broken.

Absence became visible.

Stripped of context,

what remains is admired,

while authority is lost in translation.

There’s a key misunderstanding when memory is separated from the context that gave it meaning. Museums commonly celebrate bronzes, ivories, and carvings for their beauty, but in doing so, they remove these works from the living systems that originally shaped them. To truly understand what these objects mean, we have to look beyond the display case and reconnect them with the lives and communities they once served.

In their original settings, these works were never merely objects to be looked at. Benin plaques adorned palace walls, and commemorative heads anchored ancestral altars. Carved ivories told stories of the universe, and wooden carvings played important roles in rituals and leadership. When placed behind glass and stripped of context, these objects become silent, losing their voices and much of their power.

This change forces us to confront uncomfortable questions. When Europeans looted Benin in 1897, did they take home beautiful sculptures, or dismantle a civilisation’s living archive? The invasion wasn’t simply about stealing objects. It was about breaking a system, tearing away plaques, altars and regalia that held the kingdom’s memory together.

The violence did not end with the loss of the objects themselves. Its effects ran deeper. Objects that once played central roles in governance are now displayed in distant museums behind sterile glass, lifeless. While their beauty and workmanship draw attention, the stories, authority and connections they once embodied remain obscured. What is visible is form, separated from function. Their authority, context and civic function were displaced and severed from the living systems that once made them operative.

ENGINEERED TO LAST:

Memory was designed to survive.

Built with intention.

Shaped for endurance.

Time was not trusted.

Forgetting was anticipated.

Continuity was constructed.

What is shaped with purpose

outlives the age that made it.

That is legacy.

Legacy does not lean on sentiment.

It stands on evidence.

The story of bronze, ivory, and wood is about a philosophy of continuity. Identity endures when it is made real, embedded in daily life, and protected by robust systems. These materials show that lasting memory is deliberately created, not merely a byproduct of culture.

African societies built memory so well that it endures to this day. Their objects still speak, and their symbols still carry meaning. Their systems influence discussions of identity, justice, and belonging. Built memory has weight, shapes spaces, and guides how people act.

African societies used bronze, ivory and wood with care and purpose to bear this weight. By selecting these materials, they built a culture to last, rooted authority in history, and transformed memory into a powerful force that shaped human life.

Continuity is Designed

Bronze, ivory and wood leave us a heritage that extends beyond museum displays or technical mastery. These materials teach us how societies endure. African civilisations recognised that memory fades quickly if left to chance, but it endures for generations when communities embed it in structures. They refused to separate beauty from leadership or spiritual life from politics. Instead, they combined all these elements so identity would continue through tangible things.

Today, most of those systems have been broken apart, yet even as fragments they still speak. They show us that culture is not sustained by feelings alone but by purposeful design. Authority must have a basis. Lineage must be visible. Memory must take a physical form if it is to withstand the pressures of change.

We live in an age when information grows rapidly, yet meaning can slip away. These traditions offer another perspective. They tell us that continuity is never accidental. It is shaped by repetition, ritual and form, and it survives where memory is shared, practised and anchored in lasting structures.

African societies chose bronze, ivory and wood not only for their toughness and beauty, but also for their ability to carry meaning across generations. By working with these materials, they did more than create objects; they built ways to remember, belong and govern.

This, ultimately, is the deeper inheritance. It is not only about the objects themselves but also the wisdom that shaped them. The lesson is clear: for a society to survive, it must design continuity with care, and to do so, it must give memory a form that time cannot easily erase.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history portable and accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask. He connects 8,000 years of knowledge with the present.

oriiz@orature.africa IG – @oriizonuwaje

Leave a Reply