By Oriiz U Onuwaje

Oriiz examines how the logic behind Aso Oke, Akwete, and Kente weaving shapes computation, creativity, and culture, and how it influences today’s fashion. By studying these textile arts, this essay shows how they connect ancient craft with modern technology.

The Technology of Touch

Today, technology is often seen as cold, defined via screens, silicon chips, and silent signals. We treat it as a modern invention, a rupture from a tactile, handmade past. This is a narrow view. When technology is understood as the application of logic to solve problems and communicate, a much older story appears.

With this perspective, the loom is like an intelligent machine. The weaver uses logic, and the textiles become a way to tell stories, a kind of early information technology.

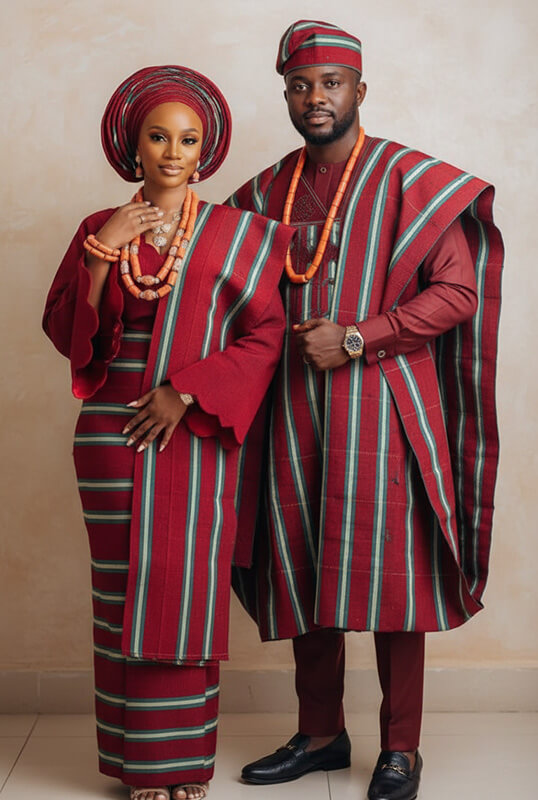

West African weaving vividly illustrates this tradition. While Aso Oke, Akwete, and Kente are the most recognised examples, many other textiles also shape the region’s rich heritage. For centuries, the Ashanti, Ewe, Yoruba, and others have practised crafts that are fundamentally computational. Kente’s detailed geometry, Aso Oke’s structural precision, and Akwete’s colourful motifs do more than decorate; they encode meaning and logic as tangible algorithms. Communities actively use these fabrics to express identity, weaving their stories and values into every thread.

This essay explores the links between African strip-weaving and digital coding. Weavers mastered logic, patterns, grids, repetition, and storing information long before computers existed. These same ideas shape both today’s data and modern African-inspired fashion.

Akwete Weaving

The Loom as the Original One Binary System

To see how weaving and coding connect, we need to start with the basics of computing: the binary system. Modern computers use two states: 0 and 1, Off and On. Everything on a screen, from a text message to a video game, is made from billions of these tiny switches.

Surprisingly, weaving works in a similar way. The main action on a loom is a simple choice between two options.

The warp threads, which run vertically, are kept tight. The weft threads, running horizontally, pass through them. At each crossing, the weaver chooses to go over or under, up or down, visible or hidden.

Traditional african attire portrait vibrant kente headwrap and dress

This process is like the source code for the cloth. Every pattern, no matter how complex, comes from thousands of simple, ordered choices, just like lines of code in a computer program.

Historians often say the 19th-century Jacquard loom was the first step toward computers, but African weavers were already running complex ‘programs’ in their minds much earlier. Instead of using punch cards, they memorised patterns, worked out detailed sequences, and wove them with great skill.

Kente: Building Blocks of Meaning

The tradition of Ghana, practised by the Ashanti and Ewe peoples, presents a perfect example of what designers call “modular design”.

In the digital world, we break down complex systems into smaller, manageable parts that we can rearrange. Kente weavers do something similar. Instead of making one large sheet, they weave long, narrow strips, usually about four inches wide.

After weaving, the strips are sewn together side by side, allowing for creative designs. Patterns in each strip can be shifted or mirrored to make new looks. Each arrangement offers many possibilities and tells its own story.

The names of Kente patterns show that it is more than just fashion; it is also an information system. The cloth holds meaning and tells stories.

“Fathia Fata Nkrumah” is a pattern celebrating the marriage of Ghana’s first president to Fathia of Egypt, thereby recording political history in thread.

“Sika Dwa Kofi” (The Golden Stool) represents the soul of the Ashanti nation.

Fetu Afahye Festival Ghana traditional chiefs in colorful kente cloth parade cultural heritage celebration African royalty ceremony Cape Coast festival

One of the most impressive patterns is “Adwini Asa”, meaning “All motifs are exhausted.” In this design, the weaver aims to include every known geometric pattern in a single cloth. It shows great skill and memory, a real-life encyclopedia of the weaver’s knowledge.

The Ewe tradition of Kente goes even further, weaving images of hands, combs, and animals into the geometric grid. Creating a curved shape, such as a hand, using only vertical and horizontal threads requires a deep understanding of the grid. The weaver breaks the curve into small steps, much like how a digital image is made of pixels. They were “pixelating” images long before computer screens existed.

Aso Oke: The Language of Social Identity

If Kente shows how to make complex patterns from simple parts, the Yoruba Aso Oke (Top Cloth) tradition shows how cloth can work as a language.

In Yoruba culture, Aso Oke is a respected means of communication. It acts as a visual signal, showing your age, wealth, religion, and the event you are celebrating. Like any language, it has rules. You cannot mix the “words” (patterns) randomly without causing confusion.

The “Classic Three” styles of Aso Oke act as the basic vocabulary of this system:

- Sanyan: Often called the “King of Clothes,” this is made from the beige silk of the Anaphe moth. It represents the raw, natural earth. It signals seniority, traditional authority, and steadfastness.

- Etu: A deep indigo-dyed cloth. The name means “guinea fowl,” referring to the tiny white speckles on the blue background. This pattern signifies wisdom, calmness, and depth. It is a quiet, serious cloth.

- Alaari: A bright crimson cloth. It signals visibility, power, and vital life force. It is the cloth of presence.

The Aso Oke artisan relies on repetition and rhythm in their work. Patterns often show a “strip within a strip.” A big block of colour is divided by a smaller stripe, which is then divided by an even thinner thread.

Akwete 01

Repeating shapes at different sizes is similar to what mathematicians call “fractals.” While Western geometry often focuses on smooth shapes like circles and triangles, African design highlights texture and repetition. The weaver measures these spaces not with a ruler, but with rhythm and counting, making a pattern that feels musical.

Akwete weaving, done by the Igbo people in southeastern Nigeria, is unique. Using a wide loom, Akwete weavers make large, detailed textiles known for their technical creativity. Their bold designs and rich textures reflect family heritage, mark special events, and continue to inspire modern fashion across Africa and beyond.

The “Human” Glitch: Perfection within Imperfection

In computer programming, a “bug” is a mistake that needs to be fixed. We expect our apps and software to be perfect and flawless. But African weaving sees “errors” differently.

In many African craft traditions, people believe only God can be truly perfect. Because of this, a small flaw, like a skipped thread or a slight change in the strip’s alignment, is sometimes left on purpose or accepted as the maker’s signature.

Today, as people question the idea of perfection in the digital world, designers are once again valuing imperfection. Generative art programs introduce randomness to avoid a uniform look. African weavers understood this long ago. The small differences in hand-woven Aso Oke, compared to the flat look of factory prints, show value and authenticity; they prove the cloth was made by hand. Here, the ‘bug’ is a mark of originality.

Weaver

The Loom as Hardware, The Culture as Software

To truly understand the weaver’s skill, we need to look at their main tool: the loom. The West African narrow-strip loom is a great example of efficient engineering.

The weaver sits with the warp threads stretched out ahead, sometimes for many yards, held in place by a heavy stone or drag-sledge. This long warp stands for memory, the cloth that is yet to be made. The heddles, which lift the threads, are the controls. The shuttle, a wooden tool that carries the thread, acts like a cursor, creating each line of cloth.

But the loom is useless without its “software”, the cultural knowledge passed down through generations. This knowledge isn’t found in books; it’s learned by watching. An apprentice observes the master, picking up the rhythm of hands and feet until the logic becomes second nature.

This way of learning keeps the tradition alive while allowing for change. When a master weaver creates a new pattern to mark a modern event, like the “Obama” patterns made in Ghana in 2008, it’s similar to a software update. The old loom is used to record new history.

Ghanaian woman in kente cloth proud expression portrait photo festive landscape

Connecting the Divide: From Loom to Laptop

Why does this comparison matter? Why should we compare a weaver to a computer scientist?

This matters because history has often ignored Africa’s intellectual achievements. When we call weaving a “craft” and coding “technology,” we downplay the skill needed to make these textiles. Recognising the logic in weaving changes this view. It shows that complex, structured thinking is not just for modern tech companies; it is part of Africa’s heritage.

Now, this connection shapes the future of African design, as digital and physical worlds come together in a new wave of creativity.

Digital Art: Today’s African artists use textile patterns to make digital art. They notice that Kente grids look a lot like the data visualisations seen in modern analytics.

New Fashion: Designers now use computer software to create textile patterns that follow the rules of Aso Oke, creating designs no human weaver has made before. This blends old logic with modern technology. Global fashion shows are embracing these trends, and major brands are inspired by the bold shapes, deep meanings, and technical details of Aso Oke, Kente, and Akwete. The influence of African weavers appears in collections from London to Lagos, Paris to New York, as designers use this digital logic in cloth and set new trends that echo the creativity of traditional looms.

Wearable Tech: As we develop “smart clothing”, clothes that can track health or change colour, the logic of the loom becomes more important. If we are going to wear our computers, then the old masters of “programmable cloth” have the most useful knowledge.

Conclusion: The Unbroken Thread

At the start, this essay promised to explore “Threads and code: weaving philosophy into cloth and logic.” We see now that these are not separate ideas. They are just different ways of speaking the same language.

The weaver sits at the loom, counting threads, measuring spaces, and balancing the tension between the fixed past, the warp, and the changing present, the weft. The coder sits at a keyboard, setting variables, building loops, and balancing the computer’s logic with the user’s needs.

Both are architects of systems, turning chaos into something understandable.

As we go further into the digital age, we should not see Kente, Aso Oke, and Akwete as just old memories. Instead, we should respect their complexity and see them as masterpieces of logic and living systems that still influence fashion, technology, and culture.

The African weaver did more than make cloth. They created an information system from cotton and silk, putting their culture’s values into a form that could travel, last, and communicate. In a real sense, they were the first creative technologists, leaving us proof that the future was never just about silicon; it was always about the thread.

The logic continues, an unbroken thread from the ancestor’s loom to the descendant’s laptop, weaving the world together, one choice at a time.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history portable and accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask. He connects 8,000 years of knowledge with the present. Oriiz also edited and served as Executive Producer for The Benin Monarchy: An Anthology of Benin History (The Benin Red Book), Wells Crimson, 2019. Author: The Harbinger: A Window into the Soul of A People: 8000 years of Art in Nigeria, Crimson Fusion (2025).

:::::::: oriiz@orature.africa IG: @oriizonuwaje