By Oriiz U Onuwaje

Oriiz presents Rhythm as a means of keeping traditions alive, showing how people remember and share what they cannot easily put into writing. Across Africa, rhythm acts as an archive, a form of governance, and a social bond, carrying memory in a way everyone can access, repeat, and protect.

Rhythm is more than a mood or background sound. It makes civilisation something you can hear and feel.

Rhythm is More Than Entertainment

Rhythm is more than entertainment. It is a system.

Before libraries and paper could keep records, societies found ways to store what mattered. Rhythm was kept not for decoration but for survival. People remembered not just for nostalgia but as a foundation for their lives.

In Africa, especially, where oral traditions evolved into complex societies, rhythm became a lasting means of maintaining identity, continuity, and order. Rhythm carries knowledge that can travel, encodes meaning that people can repeat, and helps the body remember what the mind might forget.

At its core, rhythm is the democratic technology of memory.

Why Rhythm Matters for the unBROKEN Thread

Rhythm is essential to the unBROKEN Thread.

The unBROKEN Thread is not merely a museum of old facts. It shows that Africa’s past remains active, shaping identity, creativity, ambition, and relevance today.

To share and open up memories for everyone, we need to use tools people already have. This means not just using libraries and classrooms, but also rhythm, patterns, repetition, and learning through experience.

Democratic does not mean simple or watered down. It means everyone can access it fully, without barriers.

To retail memory is to bring it out of private spaces and into everyday life. This makes heritage part of daily experience, turning knowledge into a real connection and a lasting tradition. It makes our collective history available to everyone, so people can feel heritage rather than just study it.

That’s why rhythm is not a side path in heritage work. It is one of the most reliable ways to connect with it.

Rhythm as Technology

Technology is not only about machines. It is any method that helps people keep, share, organise, and pass on meaning. In this way, rhythm is a powerful technology. It does not need literacy or electricity. It does not rely on institutions or need anyone’s permission. Rhythm moves through people, not buildings. It survives harsh climates and political times that destroy paper or silence speech. Rhythm stays visible and whole, lasting through decades, governments, and centuries without becoming outdated.

Rhythm is democratic because everyone can use it. It is open to all, regardless of age, wealth, education, or status. Young people can learn it, and older people can keep it alive. People can repeat rhythm without needing certificates or approval from elites. Unlike archives that require special access or histories that require schooling, rhythm is always available to everyone.

Even when formal education is missing or interrupted, rhythm still teaches.

Rhythm as Archive in Nigeria Today

Today in Nigeria, many people lack the literacy needed to use textbooks as a national memory. Still, the country knows itself through rhythm. Even those who have never read history can sense their heritage. They can hear belonging, feel their roots, and know when a sound is meaningful or empty. This is not a weakness, but proof that our civilisation kept its memory safe from any policy.

Today, people often trust only what is written: pages, books, certificates, and stamps. Many believe that if something is not written, it is not serious or reliable. But writing is neither the oldest nor the strongest way to remember. Ink fades, libraries burn, paper decays, digital files fail, formats change, and institutions can fall.

But when rhythm is part of people and communities, it renews itself.

Repetition as Civilisation

People might lose rhythm, but it cannot be taken away like physical archives. No one can silence rhythm without silencing the people. Rhythm is both a storehouse and a defence. It is more than an activity; it is a way for people to stay unbroken.

To see rhythm as memory, we need to see repetition as the heart of civilisation. Civilisation is not exclusively about monuments, but about systems, patterns, and discipline. It is the ability to maintain consistency over time. Repetition turns meaning into structure, structure into identity, and identity into continuity.

That’s why rhythm was as important as law in ancient societies, and sometimes even more so. Rhythm shaped work, rituals, court life, and collective efforts. It measured time, organised actions, and trained people to work together. Rhythm fostered shared feelings and understanding. In many African settings, sound did more than communicate; it shaped, authorised, and structured the community, making large-scale cooperation possible.

The Drum as Institution

The drum, especially, often served as an institution.

Calling the drum merely ‘music’ misses its true purpose. The drum could call people together, warn them, announce events, and set the community’s mood. It can signal permission, restriction, change, emergency, and authority. A society that can create such signals is not primitive—it is sophisticated and organised.

The Talking Drum

Because of this, the Talking Drum can change a room’s mood in seconds. It does more than communicate—it creates authority. It can praise someone, call them by name, or warn the group. In many places, it serves as an unwritten constitution, giving meaning, rank, and consequences through sound.

In today’s terms, it works like a ringtone—a coded signal that calls certain people to pay attention, respond, and be recognised.

When people know the codes, they respond automatically. They do not have to think about it; their bodies know what the community has agreed. At that moment, the drum is proof that African societies built systems strong enough to guide behaviour without writing and refined enough to keep identity alive through repetition.

The Body as Memory

But rhythm does more than govern. It carries personal identity, stories, and the emotions of a people. It can hold both gentleness and authority. Rhythm can highlight a special moment or bring order to a group.

Rhythm also turns memory into something you feel in your body. Most archives keep memory outside of us, in shelves and vaults. But embodied memory is different; it makes identity something you carry inside. The body becomes a book, muscles are akin to pages, breath is punctuation, and steps are like sentences.

A dancer does not just show culture; they hold it within themselves.

That’s why rhythm can be an archive even when language changes. Words may change or disappear, but the body retains its knowledge. Gestures, timing, and the way things are formed remain the same. Even if people must speak another language, rhythm can preserve their original way of expression. It becomes a hidden current of identity.

When Rhythm Carries a Nation

This is not simply a theory; it is something we can see in history.

When apartheid tried to silence South Africa, rhythm did not give in. It wasn’t just a hobby but a way to survive. It wasn’t a distraction but a declaration. People under pressure protected themselves by protecting their music. Rhythm carried what could not be spoken, kept spirits up, upheld dignity, and preserved identity as living proof.

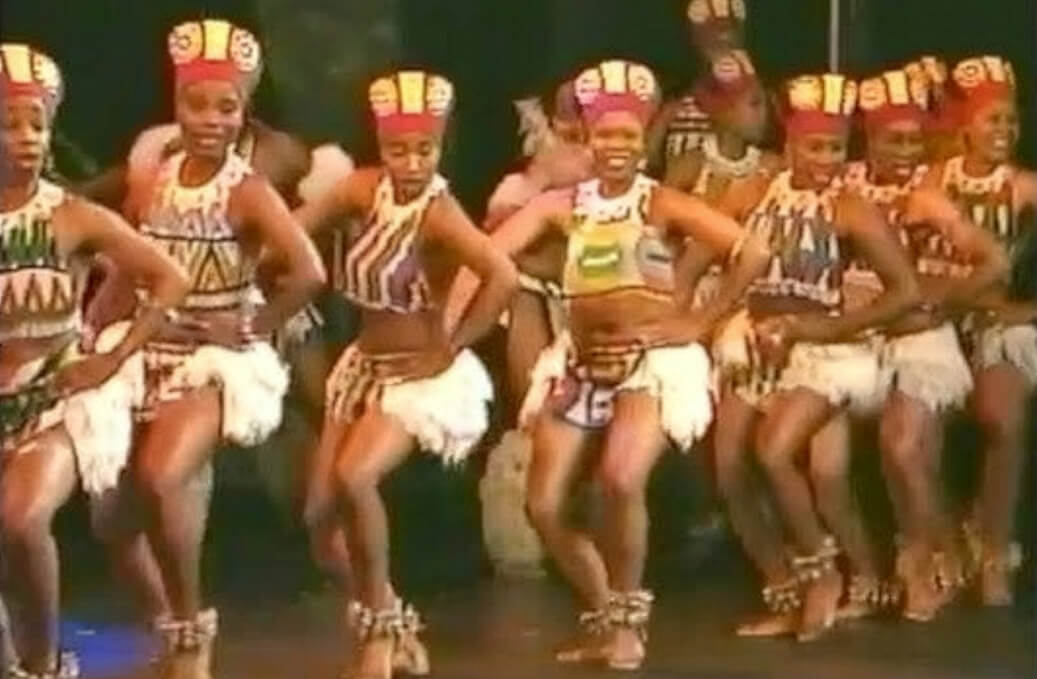

Think about what Ipi Tombi accomplished. It did more than show dance—it made South African culture visible to the world when identity was under threat. It became a symbol of beauty and proof of civilisation. It revealed what oppression tried to hide: depth, order, sophistication, and human brilliance where others tried to diminish them.

Also, think of Hugh Masekela. His music wasn’t just for entertainment; it told stories and bore witness. It carried South Africa’s emotional truth across borders. When governments use confusion to control, truth needs to be portable. Music did that. It carried memory in a way that could not be banned, turning sound into a record.

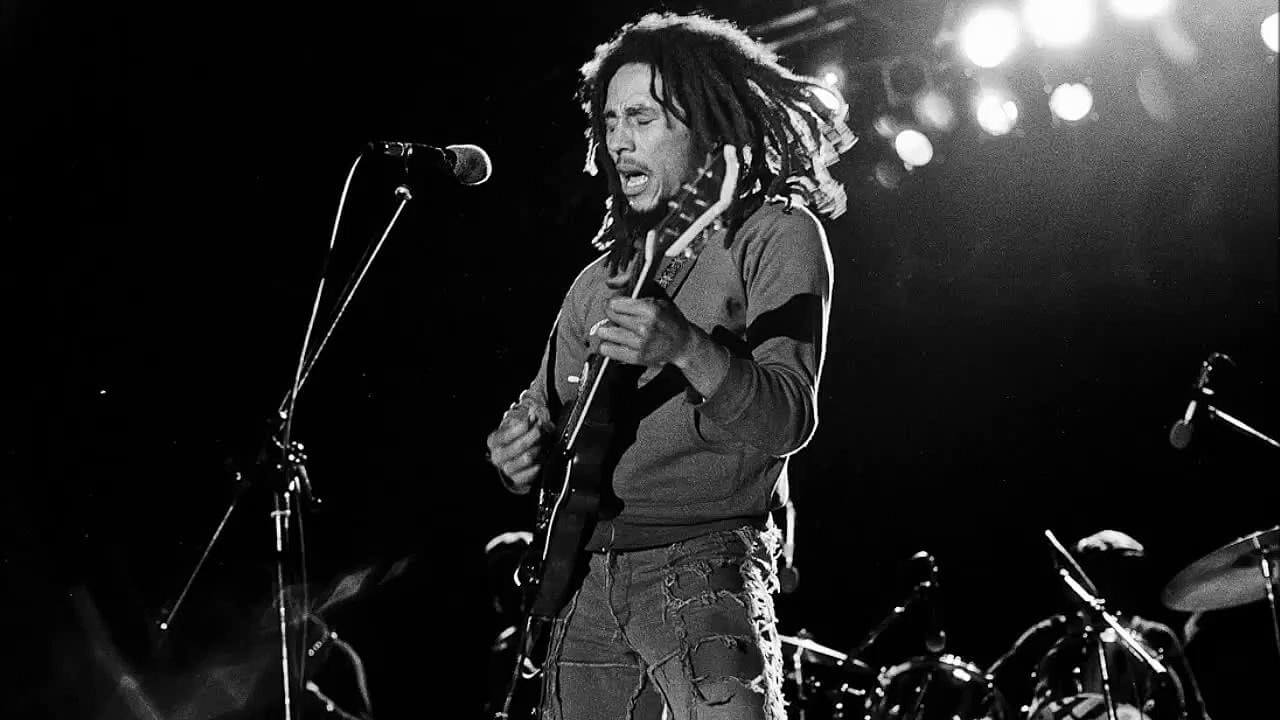

Now think about Zimbabwe. One of the most powerful moments in modern African memory was Bob Marley’s performance at Zimbabwe’s Independence celebrations in 1980. That was more than a concert; it was a ritual of renewal. Marley’s song ‘Zimbabwe’ did not merely speak of independence; it made people feel it deeply. It turned a political event into a shared memory. Independence is not just won; it is remembered, ritualised, and carried forward.

Rhythm helps people celebrate victory, not just survive hardship.

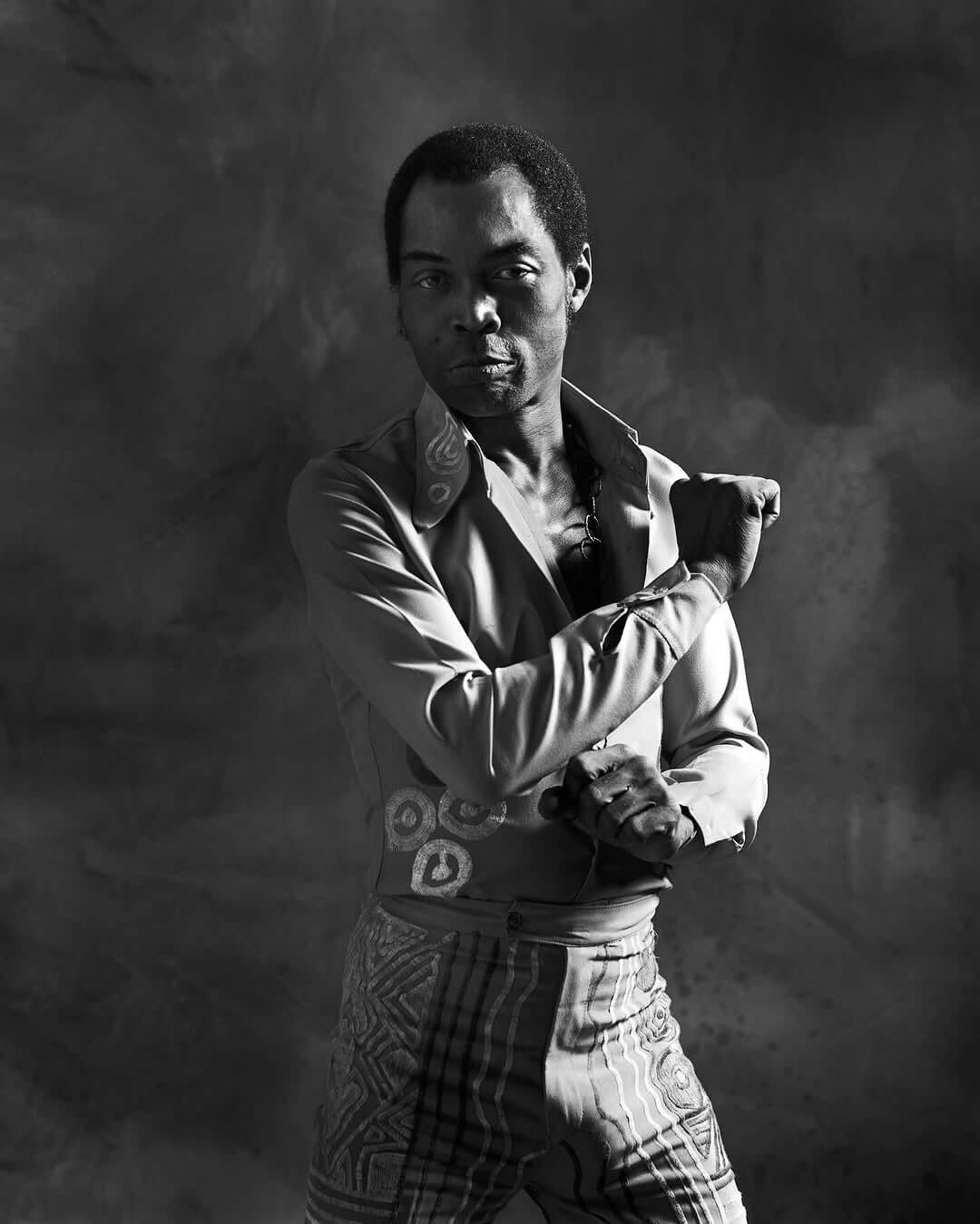

In Nigeria, Fela Anikulapo Kuti is widely recognised as a clear example. Nigeria has seen many governments and slogans, but few cultural forces have made truth as lasting as Fela’s. He did not just criticise the state—he created a musical republic alongside it. Afrobeat became a new kind of constitution, a language of satire, courage, warning, and public truth.

Fela made civic resistance feel human. He turned complex politics into rhythm. He made the street feel like a parliament and music into proof. Even people who could not read political documents could understand his music. That is democratic memory at work.

Music is One of the Evidence

That’s why music is not the only part of the unBROKEN Thread, but it is an important piece of evidence. Rhythm is one of the clearest records of African continuity.

But there is a warning here. Modern life can make rhythm less meaningful. When rhythm is taken out of context and used only for entertainment, it loses its depth. If the drum is merely a show, it loses its power. If dance is only a trend, it loses its memory. That’s why the unBROKEN Thread must be careful. Rhythm should be explained and shown as evidence, not merely as background.

This is not about making heritage just a feeling. It is about turning feelings back into heritage.

Conclusion:

Because rhythm is a kind of technology, it can be improved—not by replacing it, but by strengthening it. Rhythm can be combined with essays, artefacts, wall labels, documentaries, and modern design. It can help young people connect with heritage without feeling forced. Rhythm can make history inspiring without making it weak. It can make heritage appealing without losing its meaning. Rhythm can bridge ancient knowledge and contemporary creativity.

Rhythm is the democratic technology of memory because it turns survival into beauty and beauty into a permanent tradition. It shows that culture is not just what we keep in museums. Culture is what we repeat until it feels natural. Culture is what we live by until it becomes who we are.

And perhaps the most important truth is this: rhythm is not just something we do; it is part of who we are. Rhythm helps memory endure without needing approval. It keeps identity strong under pressure. Rhythm is how people stay unbroken.

Oriiz is a Griot, Curator, Designer, Culture Architect, and Strategist who makes African history portable and accessible to everyone: those who know, those who question, and those who never thought to ask. He connects 8,000 years of knowledge to the present.